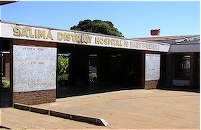

We have traveled approximately 80 kilometers from Blessings Hospital in Lumbadzi and we are nearing the east side of the old trading center of Salima. This area along the lake was once a notorious slave-trading center, but today it is a quiet crossroads community on the road from Lilongwe to Senga Bay, or the north south route from the northern part of the country to the south along the lakeshore of lake Malawi. A sign on the left side of the road indicates we are nearly there and we turn off the main road, and start up a narrow dirt road to the north. Two kilometers and we reach the Salima District Hospital.

Government hospitals in Malawi are in tiers. There are the major hospitals in the biggest population centers at the top of the tier. These are Queen Elizabeth in the southern city of Blantyre, Lilongwe Central and Lilongwe Bottom in the central region in the capital city of Lilongwe, and Central Hospital in the northern city of Mzuzu. Just below them are a tier of regional, or district hospitals. These medical facilities function as referral centers for the main hospitals. The third layer is the rural hospitals. There are a large number of these scattered all over the countryside. They feed up the food chain, or referral line to the district hospital. In reverse, the supply line comes back down that chain. From central stores the supplies feed out to each of the main hospitals, and then are fed out to the district hospitals, and on to the rural hospitals. Or at least that is the way it is designed to work. In reality there are never enough supplies. Whether Tylenol for a cold, a band-aid for a cut, rubber gloves for a surgical procedure, or simply burn ointment to ward off an infection there are never enough. The supplies coming down the chain often run out long before they reach the rural hospital out in the bush, yet it is here where the front line war on disease is being carried out. When it cannot be stopped here the hospitals up the line are overwhelmed. This is what is taking place in Malawi. The battle is being lost in the rural areas of the country because of a lack of staff, equipment and resources. In these hospitals you look to see if they have any working equipment. Do they have an X-Ray machine, and is it working? Chances are in most of the rural and regional hospitals there is none, or it has been broken for sometime and there are no funds to repair it. The surgical center in many of the hospitals is just a table with stirrups in a half-clean (or half-dirty depending on how you look at it) room with a tiny lamp, and a single light bulb. Sterilization equipment is broken, and a dingy wash pan or cooking pot is being used to boil the water that will half-sterilize the instruments. Bleach is hard to come by. Needles are used more than once, and a pair of rubber gloves for use in a surgical procedure cannot be found. Wards seldom have enough beds, and never have sheets, pillowcases or towels. A washcloth is unheard of in nearly any hospital.

Unsure of What to Expect

With this entire image in mind I turn into the drive of the Salima District Hospital and prepare to follow Suzi into the cavernous, dark interior. She has been here before. I have not. She knows what to expect. I do not. As I exit the Isuzu at the concrete car park I immediately notice the sign above the main entrance. “Salima District Hospital – Friendly To Babies”. As we near the door a staff member calls out to Suzi, “Hello Mama. It is good to see you.” I quickly learn this is a medical person that was working in the central region and has been transferred here. A promotion of sorts. We walk into the entrance and along a clean hallway. Halfway down the first corridor I pull out my notebook and pen, as well as my camera and prepare to document the inspection. Almost immediately I am surprised at the comparative cleanliness of the long, wide corridors. Some excellent planning has definitely gone into the construction of this facility, although time and the elements are definitely taking their toll on the walls, windows, doors and ceilings. It looks like the facility has been here some 50 or 60 years, and there is no indication of much improvements that has taken place since then. I have been with her to a number of rural hospital evaluations, and I am not looking forward to viewing certain parts of this one. I would much rather be back at the compound writing a book, building some sort of shelf, or almost anything, rather than walking down the dingy, smelly halls of an African hospital.

We come to the Pharmacy. There is a line of 10 or 12 people curling down the hall, each one with a prescription note in their hands, waiting for the chance to present it through the half door that is open to the public. “We’ll stop here on the way back,” she announces as we scoot on by. A quick glance on my part at the four men who were working inside, and I am surprised to see one of them dressed smartly in a crisp white uniform. Most of the hospitals no longer require their staff to wear “hospital” attire and it is common to see the workers, even the nurses, in street clothes. The potential for cross contamination must be everywhere in a government hospital, and this is certainly one of the places I would think disease and infection is spread.

Meeting an Old Friend from Mponela Rural

Our first stop is in a woman’s ward. Suzi is looking for the mattresses that have been donated to this facility. She wants to insure they are in use, and not in someone’s home where an unscrupulous staff member has sneaked them out the back door and sold them. A quick look around, and she moves out with the focus of a laser. She is moving quickly to find the mattresses, and no one seems to question our presence as we move unannounced in and out of the different departments. Along the way we pass a broken down surgery table leaning precariously out an open door, nearly ready to fall into the dust below. “Make a note of it. We have several surgery tables in the warehouse. They will probably need one to replace this one,” she tosses the words back to me as we pass. I turn to snap a picture of the table, and by the time I turn back she is almost out of sight. I run to catch up. So much for trying to remain inconspicuous! To the next ward (there are apparently more than one women’s ward), and we come face to face with the person that appears like she could be the head nurse. She smiles and greets Suzi. They know each other. She too has worked over in the Dowa District, and while I snap pictures in the ward they exchange pleasantries. Suzi tells her of our mission, and she says she knows exactly where the mattresses are located. We start to retreat from the room. In passing I notice the beds and mattresses are in better shape than in most places I have been, though there are still a number that are torn, old, ragged, and filthy. No facility anywhere seems exempt from having more patients than beds, and everywhere there are patients and caregivers sleeping on bamboo mats on concrete floors. In spite of this one being better than most, it is still not an exception when it comes to the need for more beds and mattress, along with everything else they needs.

Down another long corridor and the nurse “from back home” points us to a ward coming up on our left. True to her promise she has taken us to where we see the donated mattresses in use. I sigh in relief, and then back out of the room. Though they seem to be trying to keep them clean, the wards carry an unmistakable odor that repels everything about my “non-medical” senses. While they talk I stand out in the hallway taking notes.

Death Has Entered This Ward

Next we enter a ward area where there is a scramble of nurses taking place. A female patient has died, and the body has just been moved to a tiny side room. There is a stunned silence and puzzled expression on the 25 or 30 patients and caregivers clustered near the end of the room. They watch a young staff girl in a pink dress wash down the mattress where the human body had been such a short time before. I glance through the tiny door just long enough to note the presence of three staff members, the body, and the caregiver. The caregiver is sitting in the corner alone with her head down, sobbing. The girl who has died appears to have been only in her early twenties, and healthy. I wonder why she died. What dreadful thing has robbed her of life at such an early age? What might she have contributed if she had lived? I am reminded of the old missionary who told me on my first trip, “So many die here so needlessly.” I remember his words as I move away from the door of despair. Before we leave the department Suzi asks to talk with the student nurses. With tears in her eyes she praises the work they are doing, and the commitment they have to patient care in such a difficult part of the world. They look at her with fondness and appreciation. One has to wonder why someone will sacrifice so much when the pay is so little, and the life-threatening environment is so a part of their working conditions.

We Locate Supplies From the Project

A short distance away we interview two ward nurses. Understanding what we are looking for they quickly take us to see the ward supply storage room. Sure enough we find where the supplies have been brought to the floors, and they assure us they are using them. We add to the list a couple of things they need, and then reverse our steps back down the hall in the direction of the Pharmacy.

Reaching the Pharmacy we find the line is a little shorter, we announce we are from Blessings, and we would like to look over their stores. The smiling man in the crisp, white uniform unlatches the half door and we enter. Notebook and pen at the ready I know this is where we will make the most notes. Sure enough my “vast medical experience” proves correct, and we start making notes about the supplies on hand, and those that are needed. Suzi asks for and receives their book keeping records for the past year. She makes note of the supplies that have been sent from Blessings. Each document is properly documented, and appropriately signed. We are generally pleased with what we have found. One of the Pharmacy workers tells us the administrator is not in his office today. Apparently he has business in another part of the country.

We have successfully completed the survey tour, and we head back out the main door. A couple of more snaps of the camera, and we climb back into the Isuzu. Then there is one last glance at the sign “Friendly to Babies”, and we are off. Friendly to babies. I wonder. Maybe so, for it was one of the better hospitals we have toured in recent years, and it is evident that a dedicated staff is trying to turn back the rolling tide of disease and death. But I can’t help conclude, as we drive out of the driveway and back onto the dirt road, that by any standard of the west it is not a place where I would want my baby to be born.

|  |  |