Lumbadzi, Malawi … She was nearing 80 years of age when we first met, and, in spite of her age, she was responsible for the care of eight grand-children and great-grandchildren. The HIV-Aids crisis in Malawi has robbed the nation of a vast number of its “middle generation,” leaving grandparents, and even great grandparents to become “parents again” for large numbers of orphans.

“Everyone called her “agogo” (grandmother),” recalls Suzi Stephens, Medical Director for the Malawi Project. “Her warm expression and welcoming smile made you immediately know you were welcome to her home. But, as we looked around at her meager belongings her obvious plight in poverty made us wonder how she could survive, let alone support so many children, some not yet in their teens. For a number of years, we were her next-door neighbors, at the top of the hill above a trading center north of the capital. From time to time we would visit her for short periods of time. She did not know English, but a number of her grandchildren did, and they could easily converse with us. Often times they came to us to ask for “piece work” so they could add some money to the survival of the family. In spite of everything that piled high on her frail shoulders, she was always smiling and seemed to be very content with her life. She was a beauty to behold.”

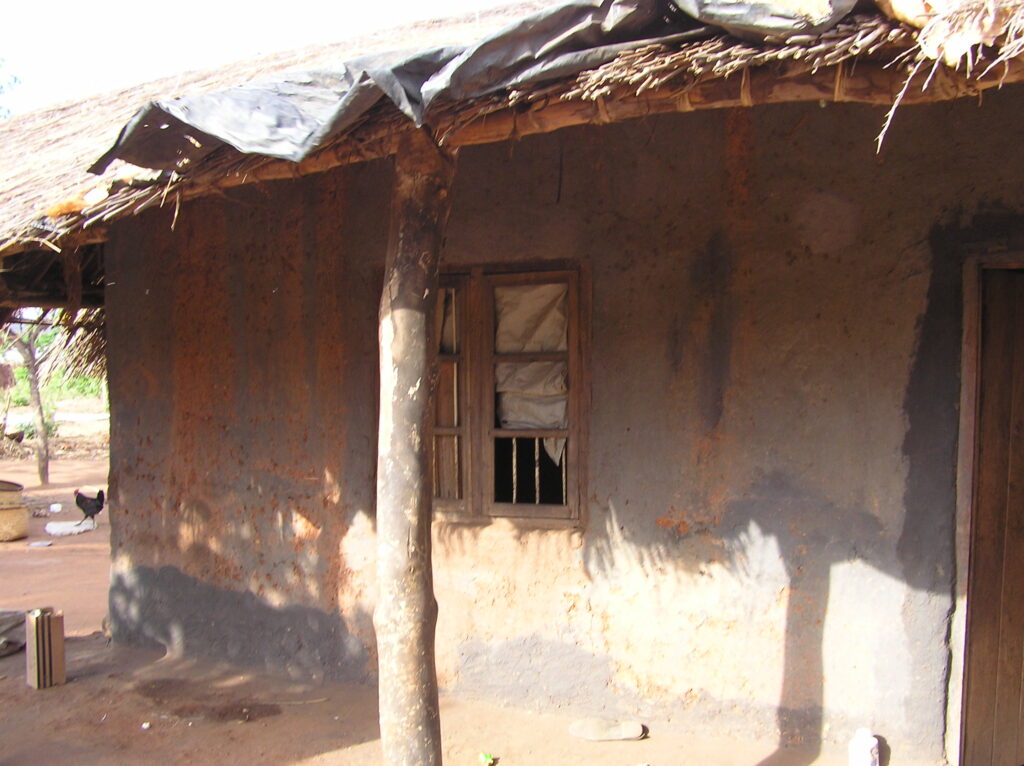

Agogo Sellina William and the children lived in a four-room brick house with mud-veneer. The veneer was badly cracked and fast peeling away from the soft brick inner structure. The bamboo-grass roof was badly in need of critical repair, and rain could easily find its way inside the house during the rainy season. This essentially open-air hut had not only the normal creepie, crawling bugs and insects, but also other more serious creatures.

The family had no running water and no electricity. They had to walk nearly a mile to a dirty river to bring back buckets of water for drinking, bathing and cooking. We could not help but wonder how they were ever well after drinking this water. On a tour of her house, which she proudly displayed to us, we saw no clothes closets anywhere, but perhaps none were needed. They had very few clothes to store anyway. They hung the only clothes they possessed on wooden pegs imbedded in the wall of the sitting room (converted at night to a bedroom). Cooking was done outside, over an open fire, using limbs harvested from trees some distance from the house. During the rainy season they moved the cooking into a small structure near the house, but they still had to walk long distances to get the wood, even when the torrential rains poured down on their heads.

Their main, (that word means almost total), source of food was stored in the bamboo bin behind their house. The bin held the maize harvest which they cultivated beside their house. A banana tree nearby added a small amount of fruit for the family for a short time each year. They have to sell some of the maize each year in order to give the children school fees, clothes, and to provide cooking oil, salt, and other items needed for their meals.

While the trading center was only about 2 miles away from her home (three and a quarter kilometers), it offered them little in the way of protection. There was no fire department, in case their house caught fire. There were a few police officers, but they had to walk their beats as they had no vehicles to use on patrol. If her or her grandchildren had a serious problem someone would have to run all the way to the trading center to get the police, and someone would have to drive them to the house, or take the time to walk there. The grocery was similar to a 7/11 in the U.S. and most of the items in the store were priced out of range for her to purchase. There was a bank, but she had no money to put in savings, a post office, but there was no one to send her a letter. She had no storeroom for food except for the bamboo structure near the house, and it was badly in need of repair. There was no income for the family, except what the children earned doing a little here and a little there. They had no social security, or government retirement plan. There was no health insurance, and no plan for what each of them would do when they could no longer work.

As we left her home that day, we marveled at the ability of these people to be so happy in spite of their circumstances. They are a testament to the validity of our mission in Malawi. People this good, with this positive of an outlook, this zest for life, deserve better. We, at the Malawi Project, are determined to help them find it.